Book Review |

The Journal of Kent History. Issue no 82 March 2016, Reviewer: Kathryn Bedford

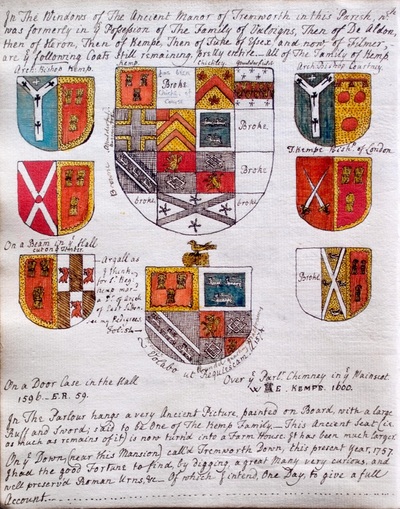

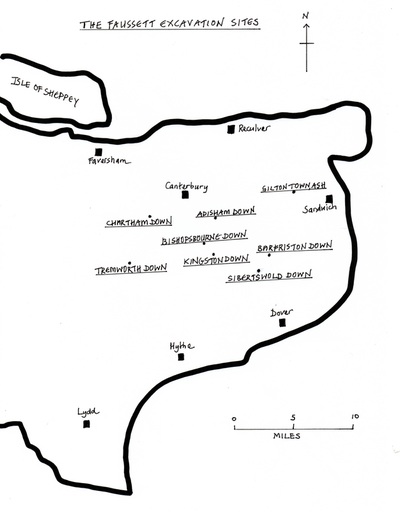

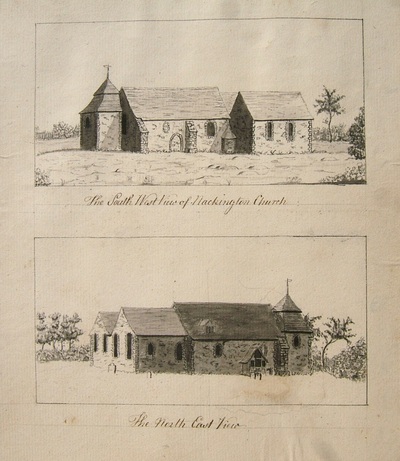

A member of a longstanding Kentish family, Faussett was born at Nackington near Canterbury and educated at Oxford. As a young man he focused on genealogy and heraldry, producing four volumes on 150 churches around Kent as well as other works. However, it was the systematic excavation of Anglo-Saxon cemeteries throughout East Kent that became his life's work, and over the course of it he discovered a substantial number of artefacts that were to help inform our views on the riches of Anglo-Saxon England. Images of some of his handwritten notes show how concerned he was with recording what he found accurately, a focus that was ahead of his time.

Much of the latter half of the book recounts the long process by which Faussett's discoveries became accessible to the public, including the famous rejection of his collection by the British Museum and images of the watercolour illustrations used for a nineteenth-century publication. These final sections give context to Faussett's life and work, showing him as an innovator respected by his peers, but also highlighting how very new our modern appreciation for artefacts as a source of historical information really is.

This book covers a broad range of topics that may appeal to a variety of people. For those interesting in family or local history there are chapters on the Faussett family, as well as their house and estates. For medieval historians there is an examination of how Faussett's finds illuminate our understanding of Anglo-Saxon death and burial. However, for me this book comes to life in the chapters on Faussett's life as an antiquary. Extensive use is made of Faussett's own notes providing detail of his working practices and ideas in his own words. These insights into the everyday issues on an eighteenth-century dig, before modern archaeological procedures had been developed, highlight the difficulties these enthusiastic pioneers faced.

Much of the latter half of the book recounts the long process by which Faussett's discoveries became accessible to the public, including the famous rejection of his collection by the British Museum and images of the watercolour illustrations used for a nineteenth-century publication. These final sections give context to Faussett's life and work, showing him as an innovator respected by his peers, but also highlighting how very new our modern appreciation for artefacts as a source of historical information really is.

This book covers a broad range of topics that may appeal to a variety of people. For those interesting in family or local history there are chapters on the Faussett family, as well as their house and estates. For medieval historians there is an examination of how Faussett's finds illuminate our understanding of Anglo-Saxon death and burial. However, for me this book comes to life in the chapters on Faussett's life as an antiquary. Extensive use is made of Faussett's own notes providing detail of his working practices and ideas in his own words. These insights into the everyday issues on an eighteenth-century dig, before modern archaeological procedures had been developed, highlight the difficulties these enthusiastic pioneers faced.