More Reviews |

Professional Review by Rosemary Sweet

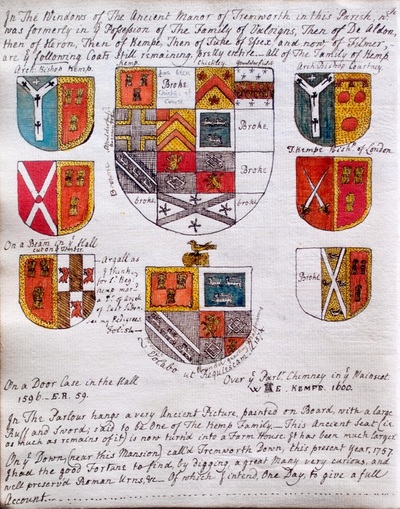

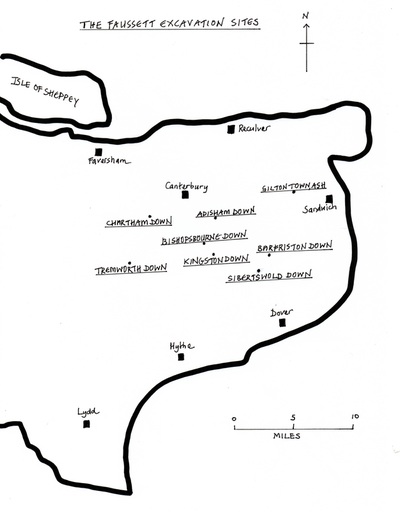

David Wright’ study is the first full length biography to have been written about Bryan Faussett, the Kent antiquary who conducted some of the most important archaeological excavations of the eighteenth century. The fact that the antiquities he uncovered were not correctly identified until the nineteenth century – Faussett being convinced that the Anglo Saxon grave goods that he discovered were in fact those of ‘Romans Britonized or Britons Romanized’ – partly accounts for this oversight. The other factor is Faussett’s own reluctance to go into print: despite being a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries he did not even contribute a paper to Archaeologia on his finds. The Faussett collection only came to national attention in the mid-nineteenth century, when his great grandson sought to sell them to the British Museum; was turned down, only for them to be purchased by Joseph Mayer, under whose patronage Faussett’s own remarkably accurate and observant notes on the graves and their contents were edited by Charles Roach Smith and published as Inventorium Sepulchrale. It was Roach Smith who identified the finds correctly and established their importance for the early history of Saxon settlement in England.

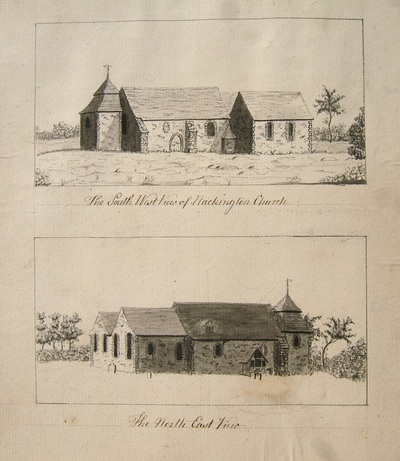

This volume is the product of extensive and detailed research, covering a considerable amount of ground chronologically (from the early eighteenth-century context to the mid- nineteenth century). It also goes beyond the narrow limits of a conventional biography to discuss the intellectual world of eighteenth century antiquarianism, the genealogies of the families of both Faussett and his mother (the Godfreys), and the afterlife of Faussett’ collection. There concluding chapters provide useful summaries of the principal types of grave goods discovered interpreted in the light of current scholarship, and potted biographies of members of the Faussett family and other leading antiquaries mentioned in the text. The book has been deliberately designed to appeal to a wide readership rather than simply a narrowly academic one: prior knowledge is not assumed (hence the helpful compendia of information at the end), it is richly illustrated, particularly with reproductions of Fairholt’s beautiful images from Inventorium Sepulchrale and it is only very lightly referenced. A bibliography is provided, but there will be many readers who will regret the decision not to reference in the text the works on which Wright’s synthesis is based.

Readers with an interest in Kentish archaeology or the development of archaeological studies of Anglo-Saxon England will find much to interest them here, not least in the fascinating detail that Wright provides on the practicalities of digging in the eighteenth century. The chief value of this book, however, is Wright’s reconstruction of Faussett’s character and the world in which he lived. Faussett was a Jacobite sympathiser and was rusticated from Oxford for harbouring a prostitute in his rooms: an incident that threatened to jeopardise his chances of a college fellowship and allowed him to assert his litigious and combative character to the full at an early stage. This was a man who occupied an ambiguous social position: he inherited landed property, but was always financially hard-pressed and constantly in search of better clerical preferment. His litigiousness did nothing to help either his finances or his chances of securing the kind of ecclesiastical position he craved. This study demonstrates very powerfully how important antiquarianism and the persona of the ‘antiquary’ was the construction of a sense of self for both Faussett and his eldest son Henry Godfrey Faussett. Antiquarianism provided him with a social network amongst with other like-minded individuals (who like him tended to occupy the lower fringes of the gentry and the professional middle classes), a sense of purpose, and sense of self.

This volume is the product of extensive and detailed research, covering a considerable amount of ground chronologically (from the early eighteenth-century context to the mid- nineteenth century). It also goes beyond the narrow limits of a conventional biography to discuss the intellectual world of eighteenth century antiquarianism, the genealogies of the families of both Faussett and his mother (the Godfreys), and the afterlife of Faussett’ collection. There concluding chapters provide useful summaries of the principal types of grave goods discovered interpreted in the light of current scholarship, and potted biographies of members of the Faussett family and other leading antiquaries mentioned in the text. The book has been deliberately designed to appeal to a wide readership rather than simply a narrowly academic one: prior knowledge is not assumed (hence the helpful compendia of information at the end), it is richly illustrated, particularly with reproductions of Fairholt’s beautiful images from Inventorium Sepulchrale and it is only very lightly referenced. A bibliography is provided, but there will be many readers who will regret the decision not to reference in the text the works on which Wright’s synthesis is based.

Readers with an interest in Kentish archaeology or the development of archaeological studies of Anglo-Saxon England will find much to interest them here, not least in the fascinating detail that Wright provides on the practicalities of digging in the eighteenth century. The chief value of this book, however, is Wright’s reconstruction of Faussett’s character and the world in which he lived. Faussett was a Jacobite sympathiser and was rusticated from Oxford for harbouring a prostitute in his rooms: an incident that threatened to jeopardise his chances of a college fellowship and allowed him to assert his litigious and combative character to the full at an early stage. This was a man who occupied an ambiguous social position: he inherited landed property, but was always financially hard-pressed and constantly in search of better clerical preferment. His litigiousness did nothing to help either his finances or his chances of securing the kind of ecclesiastical position he craved. This study demonstrates very powerfully how important antiquarianism and the persona of the ‘antiquary’ was the construction of a sense of self for both Faussett and his eldest son Henry Godfrey Faussett. Antiquarianism provided him with a social network amongst with other like-minded individuals (who like him tended to occupy the lower fringes of the gentry and the professional middle classes), a sense of purpose, and sense of self.