Book Review |

Archaeologia Cantiana. 2016 Vol. 137

Reviewer: Elizabeth Edwards

In November 1853 Edward Hawkins, vice-president of the Society of Antiquaries, said of Bryan Faussett (1720-76) whose collection was the subject of negotiations for its acquisition by the British Museum:

[Faussett] opened about eight hundred Anglo-Saxon graves in about eight or nine parishes in Kent. The contents of each grave were minutely recorded; every object capable of preservation was carefully secured, and drawings made… Perhaps so instructive a collection was never formed. It does not consist of rare, valuable or beautiful objects, picked up or purchased from dealers at various times and in various places, with little or no record, or perhaps false records of the discovery; but it consists of all the objects found in all the graves of a particular district…(p. 229)

Despite this recommendation the British Museum rejected Faussett’s collection which was acquired by the ‘assiduous collector’, Joseph Mayer, and taken to Liverpool. It was therefore in Lancashire that the first public displays and discussion of his work took place rather than in London or his home county of Kent. David Wright’s book, published with the support of the Allen Grove Local History Fund, brings Faussett back to Kent and raises his profile as one of the most influential antiquarians for the nascent archaeological discipline of the nineteenth century.

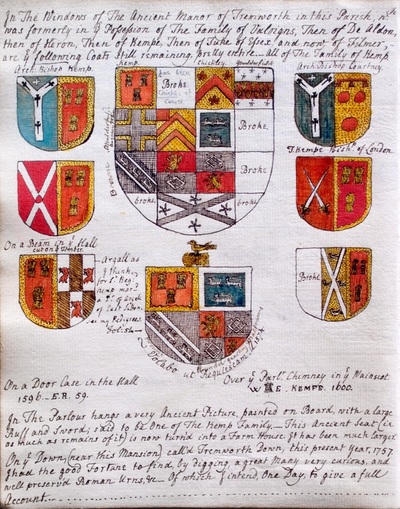

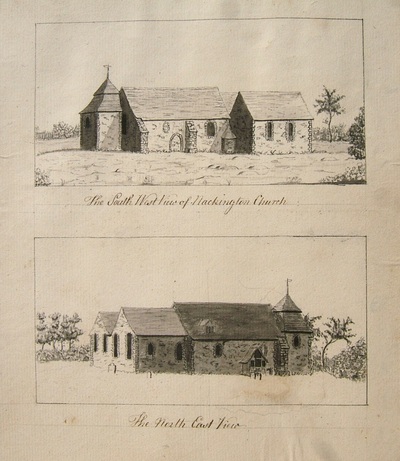

This study is much more than a biography, but the biography of Faussett runs through the whole volume, and there is detailed family history to be found in the opening and closing chapters, as well as fairly frequent references to his somewhat burdensome relatives throughout. For the keen local, family historian this provides a fascinating insight into mid- to late eighteenth century Kentish gentry life with domestic finances, building works and family matters carefully researched and reproduced. These sections are augmented by the vicissitudes of Faussett’s career as a Church of England priest, moving from his first post in Shropshire back to Kent to become curate in various parishes south of Canterbury, finally becoming rector at Monk’s Horton while remaining perpetual curate at Nackington.

One of the attractions of this book is that the content of the chapters allows them to be read as a separate articles; for example chapter 11 deals with Faussett’s house at Heppington in Nackington, the first recorded occupation of which was in 1183, but rebuilds took place over the centuries and when Faussett’s father acquired the property, through marriage, in 1710 he also rebuilt it. His ten year old son, Bryan, recorded the old house in drawings which foretold his eye for, and interest in, detail and recording. The house, in its latest guise, was finally demolished in 1969. Chapter 2 is another good essay. ‘A World of Antiquarianism’, in which Wright produces an exemplary argument on the nature of antiquarianism and history, which should be recommended to all students of local and regional history. And chapter 13 deals with ‘Three Pioneers’, James Douglas, William Cunnington and Richard Colt Hoare, all of whom, working after Fausset, further developed archaeological method. Along the way we meet other important contributors to eighteenth/nineteenth century antiquarian/archaeological research: William Stukeley, General Pitt-Rivers, and perhaps most importantly for the Faussett story, Charles Roach Smith. Wright has put each of these and many more such as Edward Jacob and Edward Hasted into the full context of Faussett’s life, work and legacy.

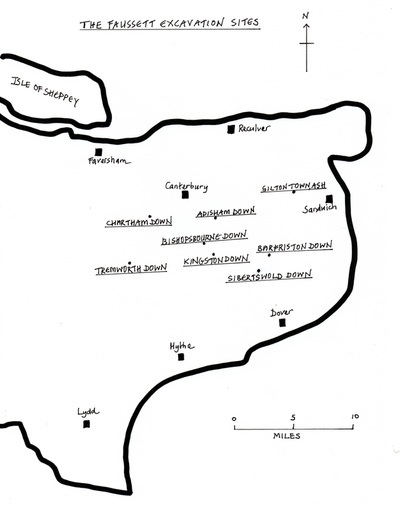

However, the core of this closely researched and detailed study is the chapters devoted to Faussett’s work as an antiquarian, the term ‘archaeologist’ was not use in the eighteenth century. Faussett’s first experience of an excavation was when he was only ten, watching Cromwell Mortimer dig treasures at Chartham Down and his enthusiasm never waned thereafter. His first two ‘campaigns’, were excavations at Tremworth Down, Crundale and Guilton Town, Ash, recorded in Chapter 5, when Faussett developed his characteristic collection and recording of every find, stimulating his thoughts on the origin, nature and rationale of burials. ‘The Summit of a Career’, chapter 8, is the very heart of this study and details the rich excavation of several hundred graves at Kingston Down between 1767 and 1773. The most notable find was the Kingston Brooch (AD 610-20) which is now held by the National Museums, Liverpool, and the clear reproduction of Faussett’s sketch and description (p.122) makes evident the value, to later archaeologists, of his work as a collector and recorder of finds, many of which would have gone the way of so much else under the plough. But Wright, like Faussett gives due recognition to all the collection.

David Wright has produced an impressive and comprehensive study of the complex life and work of an eighteenth century antiquary. And, although at times there are odd and unexplained jumps between topics, and the addition of some maps would have been useful, this is a beautifully written and presented book and the quality and appropriateness of the illustrations to the text is excellent.

[Faussett] opened about eight hundred Anglo-Saxon graves in about eight or nine parishes in Kent. The contents of each grave were minutely recorded; every object capable of preservation was carefully secured, and drawings made… Perhaps so instructive a collection was never formed. It does not consist of rare, valuable or beautiful objects, picked up or purchased from dealers at various times and in various places, with little or no record, or perhaps false records of the discovery; but it consists of all the objects found in all the graves of a particular district…(p. 229)

Despite this recommendation the British Museum rejected Faussett’s collection which was acquired by the ‘assiduous collector’, Joseph Mayer, and taken to Liverpool. It was therefore in Lancashire that the first public displays and discussion of his work took place rather than in London or his home county of Kent. David Wright’s book, published with the support of the Allen Grove Local History Fund, brings Faussett back to Kent and raises his profile as one of the most influential antiquarians for the nascent archaeological discipline of the nineteenth century.

This study is much more than a biography, but the biography of Faussett runs through the whole volume, and there is detailed family history to be found in the opening and closing chapters, as well as fairly frequent references to his somewhat burdensome relatives throughout. For the keen local, family historian this provides a fascinating insight into mid- to late eighteenth century Kentish gentry life with domestic finances, building works and family matters carefully researched and reproduced. These sections are augmented by the vicissitudes of Faussett’s career as a Church of England priest, moving from his first post in Shropshire back to Kent to become curate in various parishes south of Canterbury, finally becoming rector at Monk’s Horton while remaining perpetual curate at Nackington.

One of the attractions of this book is that the content of the chapters allows them to be read as a separate articles; for example chapter 11 deals with Faussett’s house at Heppington in Nackington, the first recorded occupation of which was in 1183, but rebuilds took place over the centuries and when Faussett’s father acquired the property, through marriage, in 1710 he also rebuilt it. His ten year old son, Bryan, recorded the old house in drawings which foretold his eye for, and interest in, detail and recording. The house, in its latest guise, was finally demolished in 1969. Chapter 2 is another good essay. ‘A World of Antiquarianism’, in which Wright produces an exemplary argument on the nature of antiquarianism and history, which should be recommended to all students of local and regional history. And chapter 13 deals with ‘Three Pioneers’, James Douglas, William Cunnington and Richard Colt Hoare, all of whom, working after Fausset, further developed archaeological method. Along the way we meet other important contributors to eighteenth/nineteenth century antiquarian/archaeological research: William Stukeley, General Pitt-Rivers, and perhaps most importantly for the Faussett story, Charles Roach Smith. Wright has put each of these and many more such as Edward Jacob and Edward Hasted into the full context of Faussett’s life, work and legacy.

However, the core of this closely researched and detailed study is the chapters devoted to Faussett’s work as an antiquarian, the term ‘archaeologist’ was not use in the eighteenth century. Faussett’s first experience of an excavation was when he was only ten, watching Cromwell Mortimer dig treasures at Chartham Down and his enthusiasm never waned thereafter. His first two ‘campaigns’, were excavations at Tremworth Down, Crundale and Guilton Town, Ash, recorded in Chapter 5, when Faussett developed his characteristic collection and recording of every find, stimulating his thoughts on the origin, nature and rationale of burials. ‘The Summit of a Career’, chapter 8, is the very heart of this study and details the rich excavation of several hundred graves at Kingston Down between 1767 and 1773. The most notable find was the Kingston Brooch (AD 610-20) which is now held by the National Museums, Liverpool, and the clear reproduction of Faussett’s sketch and description (p.122) makes evident the value, to later archaeologists, of his work as a collector and recorder of finds, many of which would have gone the way of so much else under the plough. But Wright, like Faussett gives due recognition to all the collection.

David Wright has produced an impressive and comprehensive study of the complex life and work of an eighteenth century antiquary. And, although at times there are odd and unexplained jumps between topics, and the addition of some maps would have been useful, this is a beautifully written and presented book and the quality and appropriateness of the illustrations to the text is excellent.